Ophthalmology is one of the fastest-developing fields of medicine. This is only possible by improving existing procedures and developing new eye treatment methods. We discuss the importance of the continuous development of ophthalmic techniques with Dr. Piotr Chaniecki.

What is the most crucial aspect of ophthalmology for you?

PC: Ophthalmology relies on technology. The most significant advancements in this field occurred after developing diagnostic devices and surgical techniques. The level and improvement of technology directly influence the precision of procedures and the effectiveness of direct diagnosis. The International Center for Translational Eye Research (ICTER) is focused on developing such devices. I see tremendous potential in creating new tools for doctors that will contribute to better and faster diagnoses.

As seen in Western clinics, ophthalmology in Poland is developing rapidly, but we still have a long way to go regarding technological advancement.

Why is the lack of specialized research being conducted in Poland that could help patients?

There is still much to be done. We are not lacking specialists, and I take pride in having trained several ophthalmologists, surgeons, and diagnosticians who now work as independent and excellent doctors in Polish clinics. In Poland, I observe a kind of stratification, with some places offering diagnostics and treatment at the highest global level while others require significant investment. Money is, of course, a problem, but not the only one – there is a lot of equipment in Polish facilities that is not always fully utilized. What is the reason for this? I can only speculate that it is due to a lack of ideas about how the equipment can be used for research, or perhaps it is due to a persistence in established procedures and routines. What I sometimes notice in conversations with doctors, including those working in academia, is a reluctance to change and challenge the status quo – if a diagnostic method works, why change it? If we can make a diagnosis based on average-quality results, why bother striving for more? Additionally, the entire system of training doctors requires many changes.

I can’t entirely agree with such an approach, which is one of the reasons I decided to collaborate with ICTER, as it holds great potential for the benefit of patients.

From a clinical perspective, what equipment developed at ICTER is the most important?

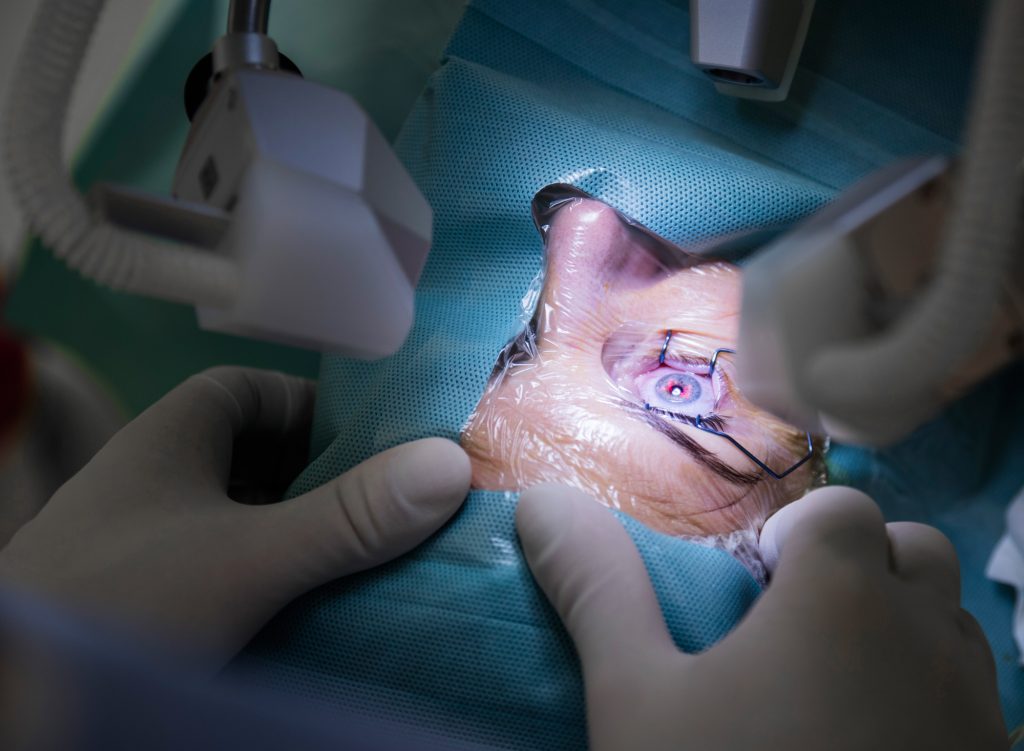

My research shows many devices with enormous potential to improve surgical procedures. I firmly believe that some of them will be “milestones in global ophthalmology.” This is not art for art’s sake. Better equipment and technology mean better diagnostics and increased patient safety during surgical procedures. I’m referring to the possibility of reducing the number of complications in surgical techniques and increasing the accuracy of diagnoses. As an experienced ophthalmologist who performs procedures according to the highest standards, I know the criteria will be even more demanding.

What are the numerical occurrences of complications in your practice?

Complications are a particularly challenging topic for every doctor. Every active surgeon encounters complications, so it is true what they say, “those who don’t operate don’t have complications.” Complications can be considered statistically, but one must approach the numbers cautiously. Even Mark Twain wrote about statistics, stating there are three kinds of lies: lies, damn lies, and statistics.

When looking at complications numerically, one would need to consider a specific procedure, such as cataract surgery. Here, sources provide values ranging from 0.3% to 15% of cases, depending on the complexity of each case. I consider complications as lessons from which I continually learn. My statistics regarding complications are within the lower range of the statistical scale.

Congratulations.

This largely depends on accuracy, which is also influenced by technology. Technology developed at ICTER will undoubtedly contribute to reducing the number of complications during surgical procedures. Another area where I see tremendous potential is diagnostics. Advanced technology will certainly increase the accuracy of diagnoses and allow us to view a given pathology from a broader perspective. Wanting to cure a patient is not enough; we must first know what to treat.

How many cataract removal surgeries with intraocular lens implantation are performed in Poland?

In Poland, approximately 300,000 such surgeries are performed annually. Worldwide, around 20 million lens implantation procedures are carried out. These numbers have fluctuated significantly over the past three years due to COVID and geopolitical circumstances.

Gene therapy is another area being developed by ICTER. What prospects do you see there?

Gene therapy primarily offers a chance for visually impaired patients due to genetic disorders, such as those suffering from Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). In individuals affected by LCA, the eye’s photoreceptors stop responding to light due to a mutation in the gene that codes for a protein essential in the visual process. Total blindness occurs around the age of 20. Research on gene therapy to remove or alleviate LCA symptoms has been ongoing for almost 15 years, and a viable treatment may soon be available. It is research institutes like ICTER that enable such progress.

Does gene therapy have a chance to become established in Polish medicine in the next few years?

We need to approach this topic realistically. Bringing a drug to market costs hundreds of millions of dollars. Research at each stage, including clinical trials, animal models, healthy volunteers, and patients, takes significant time. We are talking about a period of 5-10 years.

In addition to the research you are currently involved in with our scientists, focusing on patients with multiple sclerosis, do you plan to expand our collaboration to include patients with other conditions?

Indeed, in the next stage, we could involve age-related macular degeneration (AMD) patients. I see potential in diagnosing, monitoring disease progression, and assessing treatment effectiveness. Existing devices allow for structural imaging, which shows anatomical changes in different layers of the eye. Still, they do not provide functional imaging, meaning we cannot determine the state of crucial substances involved in vision biochemistry. Therefore, sometimes successful surgery does not result in improved vision for the patient. Such situations could be avoided if we knew beforehand whether the part we intend to repair is functioning. And this is where I see enormous potential in collaborating with the International Center for Translational Eye Research.

We want to benefit from your experience in ophthalmic practice, as it can help us refine the equipment we are developing. Do you have any guidance for us at this time?

First and foremost, for any device to be introduced into medical offices and operating rooms, it must be practical and user-friendly. It is not about the simplicity of the design or the principle of operation— not everyone needs to know how something works. Many people need to be able to operate the device. ICTER has developed many devices, such as systems for assessing retinal receptor function, which, with the suitable “packaging,” could quickly be implemented in clinics. The key is to create appropriate software so that the equipment can be operated by technicians or doctors after brief training without the need for an engineer. The second aspect is ergonomics and comfort for the patients. Let’s not forget that most patients are elderly individuals who may have mobility issues, not to mention spending 20 minutes in an immobile position during an examination. Additionally, some procedures can be particularly frustrating for them, primarily when they must focus on a bright spot they cannot see due to diseased changes in the retina. My goal is to present the clinical perspective to scientists.

Aside from my absolute satisfaction, our collaboration will benefit the patients the most. The fusion of technology, medicine, science, and practice always benefits all parties. The same will be confirmed in our case. I am eagerly looking forward to the results of this collaboration.

As are we.

Thank you for the conversation.

BIO

Piotr Chaniecki currently serves as the Chief Surgeon at the Prof. Zagórski Eye Surgery Center in Krakow. His professional background includes graduating from the Military Medical Academy in Łódź in 1996. He has also held the position of Head of the Clinical Ophthalmology Department at the 5th Military Clinical Hospital in Krakow and the Ophthalmology Department at the PCK Hospital in Gdynia.

His main areas of professional interest are anterior and posterior segment eye surgery, as well as conservative treatment of eye diseases. He is the author of a unique technique for intraocular lens exchange, which was recognized as the best surgical technique of 2019 by the American ophthalmic journal Cataract & Refractive Surgery Today. In 2016, he received the award for the best scientific paper titled “Composition of phacoemulsificated human lenses analyzed by infrared spectroscopy,” presented by the European Association for Vision and Eye Research.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

The interview was conducted by a Postdoc researcher at ICTER, Dr. Michał Dąbrowski.

Proofreading: editor Marcin Powęska, MSc.