Nowadays, eyewear is a product that combines such diverse fields of knowledge and human activity as materials engineering, advanced digital technologies, ophthalmology and optical knowledge, precision craftsmanship, industrial design and art, and even luxury brand marketing. And in this view, they fit perfectly into the translational nature of an eye research centre like ICTER. Therefore, today we would like to introduce you to the topic of eyeglasses and eyewear fashion from the perspective of a person for whom their production, individual selection and repair are a personal passion and professional challenge.

– Is it true that each of us will need at least a pair of eyeglasses during our lifetime?

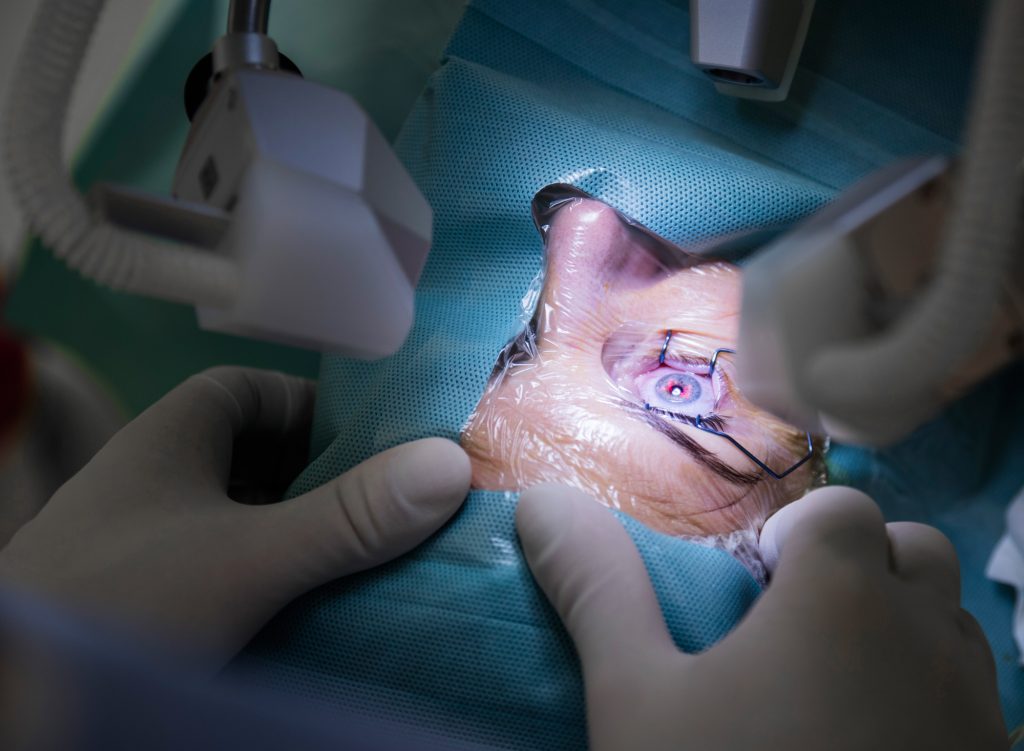

– Yes, it is true. It is inevitable. Sooner or later, even if we have not had to deal with glasses, at some point in our lives we might develop a young presbyopia, which is the loss of elasticity of the intraocular lens. Suddenly, we find that our hand needs to be longer to provide the proper distance to read the fine print. Then it is time to visit the ophthalmologist, measure the refraction, and check how much the natural lens is no longer efficient.

– So this means that we improve our correction by fitting lenses. But after all, we want to look well and fashionable, regardless of gender and age.

– Yes, and then, in addition to the choice of lenses, we are faced with the choice of frames, which is not as easy as we thought. There are a lot of factors to consider and, above all, at the end of the day you have to like yourself and feel good in that eyewear. Often, we also want it to be in line with current trends. It used to be that glasses did not mean that much as today; they were rather considered a necessary evil. One had to wear them because he or she could not see properly without them. Nowadays, we also care about looking good in glasses and having something remarkable on our face; comfort and quality of craftmanship are also important. You could say that there are waves in eyewear optics; for example, there was a fashion for wire frames, then came the style for frames made of mass (plastic), and more recently transparent. Now it is all a bit mixed up. On top of that, each of us has individual preferences. Some people prefer strong frames that are clearly noticeable on the face and will mark their character, and others prefer softer, more subtle frames. It is essential that it is stylish and comfortable and that the patient feels good in the eyeglasses because it is a prosthesis of our sight, after all.

– Who sets the fashion trends in eyewear?

– These days, major fashion houses mainly create fashion trends for ladies and gentlemen through their biggest, often exclusive, and most recognizable brands. In almost every seasonal collection, eyewear – mainly sunglasses but also corrective frames – is an integral part of the designs presented on the catwalk. Trends are also currently set by celebrities and influencers. Famous people, artists, and so-called stars often appear in eyeglasses, wearing increasingly exciting models, especially sunglasses, including those from the catwalks. Thus, they are arousing the interest of at least part of the public. We often have patients who ask for frames that a particular celebrity wears. This is interesting insofar as each face needs a slightly different frame. The one in which Christopher looks elegant and chic will not necessarily satisfy Charles, who also may feel uncomfortable wearing such frames. You also need to pay particular attention to individual preferences when choosing glasses.

– Eyewear fashion is mainly shaped by the dictates of fashion houses. But other trends may impact on what we wear every day, too. A strong trend at the moment is ecology and sustainability. What does this trend look like in eyewear fashion?

– More and more manufacturers use recycled materials to make frames for sun and eyeglasses. We collaborate with a company that produces frames from raw materials from recycled ocean rubbish. More and more admixtures of wood and other natural materials appear in frames, which were initially poorly used due to their fragility and breakability. Nowadays, they are enriched with special accelerated plates, which make the luminaire more flexible and usable for longer.

– Speaking of materials, what other materials besides those mentioned are used to create the frames?

Obviously, plastic. Today it is characterized by its enormous strength and lightness. These are usually thick frames, although lightweight, and also quite soft and therefore recommended especially for children. For this purpose, zylonite, or cellulose acetate – a hypoallergenic plastic – is used, and epoxy resin, which, when heated, is very malleable and easily adapts to the shape of the face. Metals such as surgical steel, aluminum, titanium, or beryllium are also used to manufacture frames. It all depends on the customer’s preference and wallet, as some frames, such as titanium, can be pretty expensive.

– Can you give a second life to your old eyeglasses?

– Yes, some companies and foundations, also in Poland, collect used or unused frames and eyeglasses from opticians. In fact, I always have frames in my salon that I will not use, also for spare parts when repairing my customers’ glasses. From time to time, we pack them up and send them to the place where the frames are refurbished. Then a group of ophthalmologists and/or optometrists go to third countries and make glasses for people locally from these collected frames, so that they can be reused so that someone enjoys it. We walk around in a frame for a few years and it doesn’t wear out completely; after a few treatments, it can be refreshed. These are also helpful training materials for schools that train personnel of optical stores and optometrists, and this field of education has been growing rapidly in Poland for at least 10 years.

– Can you tell us about your adventure in optics?

– My company is a family business. The business was developed by my father and he taught me the craft from childhood. I cannot imagine doing anything else. I am fascinated by glasses, optical technology, the selection of frames, how the eyeball is constructed, how the image forms on the retina. My dream is to go into optometry in the future. The current direction of optometry in Poland helps doctors to focus on the treatment of eye diseases, not only on the selection of vision correction. This is all the more so because technologies are becoming more and more advanced, the designs of the spectacle lenses themselves are basically changing from year to year, and the ophthalmologist is not necessarily aware of these design changes. The doctor focuses on the diseases, the final correction of the vision defect remains at the level of the personnel of optical store. When selecting glasses and frames, I prefer to check the prescription I get from the client, especially if it is for progressive or relaxed lenses, where there are progression channels or aberration zones. These are not big differences between the main prescription and my correction, often 0.5 dioptres or a slightly altered cylinder axis, but we are able to fine-tune this initial examination so as to squeeze the most out of the lens. Today’s lenses are more precise and require opticians to be more precise in their measurements as well. They are made using digital technology, where every 0.1 mm in fitting height or pupil distance or progression channel fit makes a huge difference to the patient. This significantly impacts patient’s comfort and adaptation to the new eyeglasses.

– Talking about technology, can you please tell us whether augmented reality is being used in the selection of frames, for example. Is this happening?

– Yes, there are optical companies that are experimenting with it. The patient then stands in front of a device, a computer takes a scan of his or her face, then, based on an algorithm, calculates what frame would be optimal for that face and prints it in 3D. How this works in practice, I haven’t seen yet, but I’m curious to see if this selection – which is basically pure mathematics – will work in practice. After all, every face is different, and of course the computer can make very accurate scans, but whether this exact calculation will be good for a particular patient may always be a matter of dispute, as subjective issues come into play here, of one’s own judgement, which the machine is unable to assess. Of course, it is possible to write a program in which the patient can enter his or her preferences for such a setting, but there is no certainty that the final result will satisfy the patient. This already works in some places, but it is still not commercially applicable on a large scale.

– Now, we often have several eyeglasses with different frames, especially when we have a visual impairment and do not want or cannot use contact lenses. We treat them a bit like a perfume or a watch. I am wearing this outfit today and I would like to wear matching eyeglasses.

– Exactly, for me this is about sunglasses. I have a whole lot of them and I cannot get rid of any of them because I like them all. Today, glasses are an integral part of our image, whether we have a visual impairment or not.

– While we are on the subject of functional glasses, what other types of glasses are still used in different areas of life?

– There are, for example, sports glasses whose lenses are dedicated to golfers, pool players, runners, etc., who for various reasons cannot use contact lenses. Often these are special lenses, especially progressive lenses, designed to provide optimum functional comfort when playing specific sports. For example, for colliers who need to have full-spectrum vision. There are also safety glasses for people who work in difficult conditions – welders, turners – in which there is also the possibility of correction. An interesting example is ballistic goggles, designed mainly for advanced shooters over the age of 40, who encounter the problem inherent in all presbyopes, wanting to see the bow and target like in the good old days, but whose visual defect no longer allows them to do so. And this is also where dedicated glasses have their uses.

– Where do you get from the eyewear that you offer? What are the leading countries in the production of frames and how does Poland rank against this?

– Poland ranks quite well, we have more and more domestic manufacturers of frames and the quality of these frames does not differ from their foreign competitors. The frames are really well made, high-quality materials are used in their production, and in terms of price they are definitely more friendly than foreign ones. I also have a wide range of frames from Italy and France in my showroom, as I love them for their design and often handmade, they are perfectly shaped and provide a high wearing quality. I also appreciate frames from Spain, which explode with colour and bold, modern styling, and are very lightweight and fun to wear. Polish frames are brilliantly made, but the design itself still needs work, and in this respect, we often take inspiration from foreign manufacturers.

– How do you see the future of the eyewear industry?

– Since I have been in eyewear optics for more than 20 years, the industry has undergone a real revolution. Changes are happening right before our eyes, and they are being set by lifestyle, as customers’ needs are changing along with lifestyle changes. Hence the incredible popularity of sunglasses, which, in addition to their protective function, are actually a fashion accessory, new ideas from frame manufacturers for shapes, overlays, striking temples – everything that allows you to stand out from the crowd, emphasize your individuality and often also your material status. When it comes to design, many frame models are making a comeback. It could be said that every type of frame will have its time, albeit in a new guise. Also, material technology allows for incomparably more in design than before.

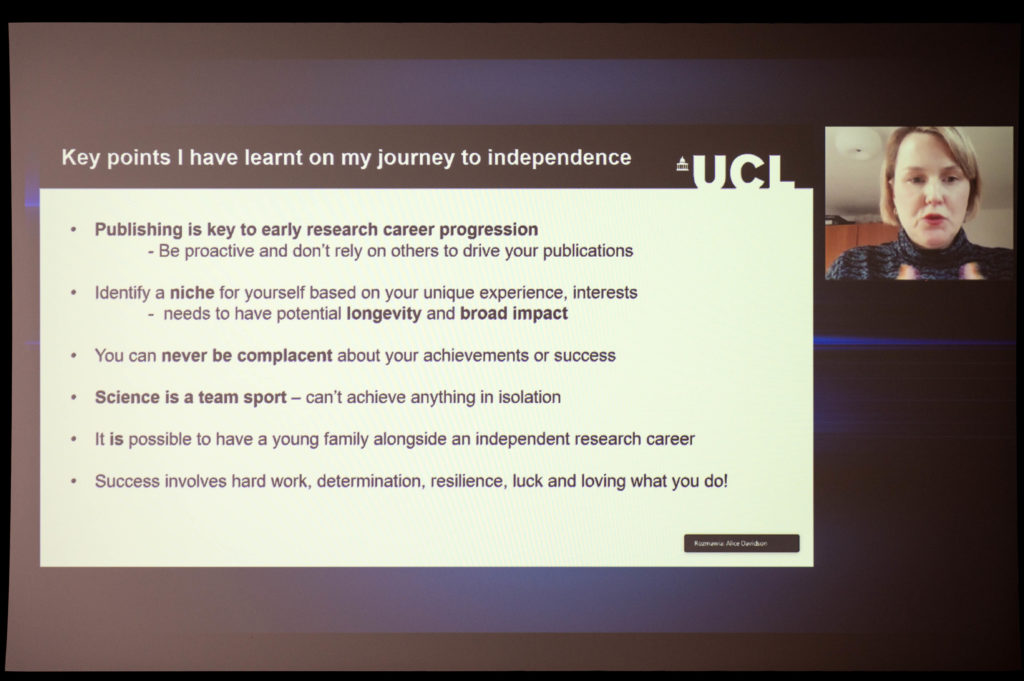

Modern software on the ground of optical services is also entering the salons, including biometrics and VR technologies, which make it possible to acquire the extensive amount of data necessary to make individualized lenses optimally tailored to the needs of the individual patient. Such software is also being developed in Poland. In this respect, we are collaborating with Szajna in Gdynia, which is a manufacturer of progressive lenses and offers a VR diagnostic device to track the behaviour of the eye in real time with different accommodation and vision conditions. The data thus acquired provides additional information about the patient’s eye behaviour under different conditions and enables the optimal selection of progressive lenses.

The future is happening today, and the optical industry itself has great potential for growth, not least because of the ever-increasing number of people requiring vision correction at different stages of life. I follow the latest eyewear trends with curiosity and attention in order to be able to provide my customers with a high-quality product that fully satisfies them medically, functionally and aesthetically.

– Thank you very much for meeting me and I wish you the best of luck in the further development of your business!

The interview was written by Joanna Kartasiewicz, Research Funding Manager, in collaboration with Jarosław Bugaj, owner of Studio Optyk Optical Store in Wolomin, near Warsaw. https://www.facebook.com/studiooptykwolomin/

Special thanks to Szajna company for the opportunity of testing their VR solution.